Byard Ray, Manco Sneed & Mike Rogers (FRC505)

by Blanton Owen

This paper, slightly revised, was originally presented as part of a panel at the American Folklore Society meeting in Los Angeles on 26 October 1979.

It is tempting to take the easy route when studying a region’s folk life by dealing with “items” as if they exist and have existed without much tampering with by human beings. It is easy simply to collect “stuff” (barn plans, tales, ballads, and fiddle tune!) and, once collected, to shuffle and analyze these things at will. This is not to say that such endeavors have no value, for they can and do. But if one is interested in the operating rules which help govern an item’s development, persistence, or demise, one must look beyond the item itself. Especially when dealing with expressive and performing arts, it is absolutely necessary, as Henry Glassie has suggested, to “move inward from the item to inspect the individual and his culture,”1 in order to understand better both the observable characteristics which determine and limit that individual’s expression or performance, and some of the reasons-psychological, social, and cultural-which allow and direct this person to do what he does in the way he does it.

One of the results of studying traditions primarily through items and without enough regard for the individuals who made them is that we, as folklorists, delude ourselves into thinking we come to know that tradition. Such an assumption is pretentious. At best, we may learn something of the normative patterns within a tradition — the “norm” or “average” — but we can know nothing about that tradition’s limits — if indeed it has limits. I use the term “limits” loosely, for we all know that folk life of all sorts continually shifts and adjusts and refuses to be plugged neatly into any sort of limiting pigeon hole. Flexible limits do exist though, at specific times and places in all traditions. Without boundaries, how do we know when any “traditional” form is no longer traditional and is, in fact, something else?

In order to understand more about a particular tradition’s limits, we must deliberately and knowingly seek out those people — again’ past and present — who can help us determine them. It is for this reason that folklorists are drawn to the most innovative and creative participants within a given tradition. It is usually through these innovative few that we are able, with care and time, to determine the limits of acceptable artistic creativity possible within a tradition. The problem with concentrating on these individuals, though, is the danger of assigning traditional status to elements which, in fact, have gone beyond the realm of the traditional aesthetic. If this is done, our picture of the tradition as a whole will be skewed if not absolutely wrong.

When we run across one of these few innovative performers, especially within a fiddle tradition, it is essential to learn as much as possible about why and how this person developed into the kind of performer he is. Family histories and sources of influence upon his style and repertory must be deter-mined. With this background information in hand, it is then possible to place the musician within his broader tradition and to determine how he has or has not expanded the limits of creative possibilities within the tradition.

Studying the fiddle style of Manco Sneed presents an example of this research process. He is an innovative, creative performer. Investigating his development presents a sense of some of the limits of traditional Southern fiddle styles.

An investigation of the development of Manco Sneed’s style best begin with a look at his family and personal background. Manco Sneed was born on February 18, 1885, in Jackson County, North Carolina, which lies on the eastern slopes of the Smoky Mountains. Prior to Andrew Jackson’s Cherokee removal in 1838, Manco’s grandfather, an English trader, moved from Charleston, South Carolina, into the North Georgia area of the Cherokee Nation where he married a full-blooded Cherokee. Sometime prior to 1885, Manco’s parents, John and Sara Lovin Sneed, moved to Jackson County from Hiawassee, Georgia, which lies just across the state line. John Sneed, who was half Cherokee, had a wide reputation as a showman fiddler. He played left handed without reversing the strings on his fiddle and did a lot of showy trick fiddling. It is said that when his wife got put out with him, he would strike off down the road playing the tune “Going Down This Road Feeling Bad” with the fiddle behind his back. When Manco was about twelve years old, he moved two counties west with his family to Graham County, North Carolina. It was while he was here that Manco really devoted energy to learning to play the fiddle. His two older brothers, Osco and Peko, also played music, but they never developed their abilities beyond the rudimentary stages. His youngest brother, Cameo, was known as a dancer, but he apparently had no inclination to make music himself.

While in Graham County, Manco made the acquaintance of Dedrick Harris, an excellent fiddle player by all accounts who was originally from Flag Pond, Tennessee, but was then living in Andrews, North Carolina. The very young Manco and much older Dedrick Harris must have been quite a team al the social events where they playedthe both played fiddle and banjo so they could take time about on each instrument as the inclination struck them. Manco said however, that he normally played banjo and Harris the fiddle.

Harris’ influence on young Manco Sneed was great; almost one quarter of the tunes Manco has recorded, he attributed to Harris. Manco spoke of Harris almost with reverence and took pride in noting that he was the only person still living who played Harris’ tunes in Harris’ style. Harris’ reputation as one of western North Carolina’s best fiddlers is still alive today. In a recent conversation, banjo maker Homer Locust told me that Harris and Manco Sneed were, in Mr. Locust’s opinion, the two best fiddlers this country ever produced. Harris, in addition to participating in the famous 1925 fiddler’s convention in Mountain City, Tennessee (where he is pictured with his twin brother, Demp, on the cover of County LP #525) also recorded commercially twice in 1924, he did four sides in New York with Ozzie Helton for Broadway Records, and in 1925, he recorded “Cacklin’ Hen” for Okeh in Atlanta.2

Another man whom Manco knew and played music with while in Graham County was Mac Hensley. Though Manco attributes none of his tunes directly to Hensley, he did play a lot of music with him and remembers him as being a good old-time fiddler, though not quite as good as Dedrick Harris. Manco also played music with Mac Hensley’s nephew, Fiddlin’ Bill Hensley who, according to Manco, was a pretty good fiddler, but played a little rough and drank too much.3

In about 1903, John Sneed moved his family to the Cherokee Indian reservation. Although John was one-half Cherokee, his move seems strange, (especially in light of the fact that John, according to Manco’s Son-in-Law Nat Brewer, “hated the ground the Indian walked on.” In fact, John carried a large walking stick loaded with lead with which he was known to have knocked more than one Indian senseless. He was also supposed to have used a ten-gauge shotgun to shoot at loud Cherokees who passed near his house on their way through the gap between Soco and the village of Cherokee. At any rate, the Sneeds, with their eighteen-year-old son Manco, who was right at the height of his learning stage, moved onto the reservation.

With this move, the social outlets for the music Manco had learned while in Graham County almost completely disappeared. There were no parties and dances in Cherokee such as he had enjoyed around Robbinsville and Andrews. The few dances he played for after his move were strictly for “white boys and girls.” In his typically understated manner Manco summed up the situation when he said, “these Cherokees, they don’t rnake music much.” So, except for occasional visits to a Dr. Bennett’s place in Bryson City 4 (where he played for partying railroad workers) and occasional visits to his former music friends, especially Harris and Mac Hensley, his frequent get-togethers with other musicians ceased. His lack of contact with other regional white musicians was further hampered by the mountainous topography and poor roads.

With his move to Cherokee the social base for the dance music Manco played when he was first learning was virtually lost. Faced with this situation, Manco was forced to make an important decision; to drop his no longer socially relevant music or to reevaluate it and continue playing. For several reasons, he chose the later.

When Manco Sneed moved on to the Cherokee Reservation and the social outlets for his Anglo-style fiddle music disappeared, his music gradually shifted away from the performance of “frolic” pieces toward a higher development of more intricate and melodically complex tunes. Based on what Manco had told me, as well as what his sons and daughters have said, at one time Manco could play for hours and not play the same tune twice. I have no doubts of this; it seems inconceivable that someone with Manco’s technical ability would not have played a fairly large number of tunes, especially during his learning years. By the time he was in his early seventies until he died in 1974, however, this was not the case. The total number of his recorded tunes of which I am aware is ridiculously small, a total of twenty-eight separate tunes, including two so-called “Cherokee pieces.” In 1959, Peter Hoover recorded twelve of his pieces.5 During the three year period of 1970 to 1973, I recorded only five tunes not previously recorded by Hoover. I recently heard two tape recordings of Manco made in the early and mid-sixties by his son-in-law, Joseph Laurel Johnson (who was himself a good fiddler from Atlanta), on which Manco played a total of thirty-four tunes, but there were only twelve tunes I had not heard before. His total recorded repertory of which I am aware, therefore, stands at twenty-eight separate tunes.

On one of these tapes, recorded in the early 1960’s by Manco’s son-in—law, Manco on all nineteen tunes is accompanied by Mr. Johnson, playing two-finger style banjo, and Manco’s daughter, Mary Freeman, playing guitar. It is significant however, that-accompanied or not, Manco still played his basic repertory of tunes, a repertory consisting of tunes which, for the most part, are incredibly difficult to accompany. This tape is interesting, for it readily illustrates the difficulties inherent in attempting to accompany complex melodies. Although, for example, many of Manco’s tunes (such as “Georgia Belle” and “Snowbird”) have “G” to “F” chord Progressions, neither the guitarist nor the banjo player made any attempt to change accordingly. Although discordant accompaniment sometimes is deliberate (“it sounds better that way”), this instance was not deliberate.

Of the twenty-eight different tunes recorded by Manco, only about seven comprise his obvious favorites, his core repertory. On almost every tape made of his music, he repealed these same seven tunes. In fact, on a tape I made in 1970 and on another I made in 1973, even the playing order or the tunes is almost the same. Manco’s seven core tunes are:

- Katy Hill

- Forks of Sandy

- Polly Put the Kettle On (father)

- Snowbird (J.D. Harris)

- Georgia Belle (either J. D. Harris or Mac Hensley, uses a G to F chord progression and bow triplets)

- Grey Eagle (J. D., Harris)

- Billy in the Lowground (J. D. Harris)

Manco’s total recorded repertory of which I am aware is, in addition to the above seven pieces:

- Cumberland Gap

- Rocky Palace

- Blackberry Blossom (learned in the thirties from Fiddlin’ Arthur Smith radio broadcasts)

- Newport Breakdown (Blind Wiley Laws)

- Waggoner

- Lady Hamilton (probably J. D Harris)

- Paddy on the Turnpike

- Ragtime Annie

- Florida Blues (Fiddlin’ Arthur Smith radio broadcasts)

- Under the Double Eagle

- Sally Johnson

There are ten tunes which I have so far been unable to identify, including the two “Cherokee pieces.” It seems that as time passed, Manco continually refined his music. He let slip all but those very few tunes which must have seemed to him special. He invariably chose to maintain melodically complex pieced, pieces that allowed plenty of room for individual development and creativity. Not surprisingly, the tunes which he apparently once knew but eventually dropped from his repertory are those normally considered “frolic” or strictly dance pieces.

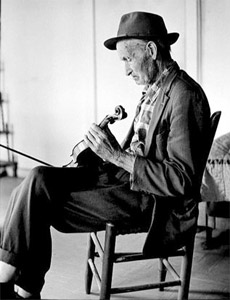

With the doors open for him to do virtually anything he felt like doing with the tunes he kept, what he actually did clearly helps define the creative limits possible within his tradition. For example, though the tunes he chose to keep are all melodically complex, unlike some fiddle: players in other traditions, he chose only lo vary slightly the melodic lines themselves. That he did, rather, was to develop very complex bowing and fingering patterns, but all the while not obscuring the basic melody.6 His playing style, which was intricate and subtle, was also very conservative in motion. When playing sitting down (which was the only way I ever saw him play), he always sat as shown in figure 19 right leg crossed over left, fiddle placed on the right side of his chest, bow held between the limb and the second joint of the index finger, and the fiddle resting on his left wrist. He never moved his bow more than about six inches. He played very quietly and for very short times, seldom playing a tune for more than a minute.

As a young man, Manco Sneed learned and played the music commonly found around his home area of Graham County. He apparently played both for social occasions and for himself, and learned tunes from several sources. It seems, however, that he deliberately sought out certain “old timers” who played, as he called them, “the old-time pieces.” Most notable of these “old- timers” was Dedrick Harris.

With his move to Cherokee in 1903, just when he was at the height of his learning years, Manco entered a society and culture which had virtually no place for Anglo fiddle music. Thus separated from the social outlets necessary to maintain his frolic pieces (and having no desire to travel extensively in order to maintain such pieces7 ), he soon began to reevaluate his repertoire along more personally expressive lines. As time went by, he gradually dropped all but a handful of tunes which seemed to him special and worth keeping. While playing these tunes, he also managed to develop a complex playing style perfectly suited to these remaining pieces. It seems that both his complex individualized style and limited repertory are his making a choice — over a long period of time— to maintain only certain personally satisfying tunes.

Transcriptions

The three transcriptions below illustrate, from most straightforward to most complex, Some basic characteristics of Manco Sneed’s style. “Katy Hill,” which he clearly distinguished from the similar “Sally Johnson,” is perhaps his most “breakdownish” and rhythmically regular piece. In this piece he uses numerous double-stops, a stylistic trait he only occasionally uses in other tunes. What he prefers to do in most of his tunes is bow a low string — usually the G — and let it sound as a drone while playing the melody on the higher strings. Note that although this is one of his fastest pieces, it is, in fact, fairly slow.

“Georgia Belle” and “Polly Put the Kettle On,” like several other of Manco’s pieces, have a G to F chord progression. Both are good examples of Manco’s preference for melodic and rhythmic complexity. “Polly Put the Kettle On” is especially indicative of the rhythmic subtlety and complex bowing patterns so well developed by Manco and “Georgia Belle” shows his use of bow triplets well, Both tunes are also noticeably slower in tempo than “Katy Hill.” The recordings from which these transcriptions were made are from a recording made on June 8, 1970. at Mr. Sneed’s home, on a Nagra recorder on loan from the Smithsonian institution, Although Manco was playing in G position on the fiddle, he was tuned one full step low, hence the actual pitch was F. His fiddle, therefore was tuned FCGD.

The transcriptions, originally done to actual pitch, have been transposed as if the fiddle were tuned to G standard. Thanks to Teresa. Broadwell and James Dooley for their patience in transcribing these tunes.

Notes

- Henry Glassie, Pattern in the Material Folk Culture of the Eastern United States. (Philadelphia. 1968). p.15.

- This information was obtained in conversations with Charles Wolff, Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, Tennessee, and Joe Wilson, Director, National Council for the Traditional Arts. Washington, D.C. at the 1979 American Folklore Society meeting in Los Angeles.

- For an interesting account of western North Carolina fiddle music in general and “Fiddlin” Bill Hensley in particular see: David Parker Bennett, “A Study in Fiddle Tunes from Western North Carolina,” unpublished MA thesis in music, The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 1940.

- I am not certain that David Parker Bennett and “Dr. Bennett” are related, but suspect they are. D. P. Bennett is also from Bryson City, North Carolina.

- The Hoover Collection, of which these tapes are a part, is deposited in the Archive of Traditional Music at Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana. [*Editor’s note: parts of Peter Hoover’s collection have been released by the Field Recorders’ Collective in the “500” series, available on the store pages.]

- See Henry Glassie, “Folk Art,” in Richard M. Dorson, ed., Folklore and Folklife (Chicago, 1972), pp. 271-72, where he makes the point that in folk art of all kinds the basic form of the art is not obscured beyond recognition by ornamentation: “no matter how many curls or swirls the folksinger employs. The skeleton of the melody remains apparent …”(p. 272).

- This lack of enthusiasm for travel was apparent in conversations with Manco. In addition, his children and friends echo the same sentiment.